The city of Ravenna is located in the marshy area in the eastern part of the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna just a few kilometers from the Adriatic Sea and 115 km down the coast from Venice. Today it is a relatively tranquil city not quite as big as nearby Bologna (65 km to the west), but it is steeped in the history of late antiquity and loaded with UNESCO World Heritage Sites filled with beautiful mosaics, several of which are easily recognizable from many history textbooks.

The city of Ravenna is located in the marshy area in the eastern part of the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna just a few kilometers from the Adriatic Sea and 115 km down the coast from Venice. Today it is a relatively tranquil city not quite as big as nearby Bologna (65 km to the west), but it is steeped in the history of late antiquity and loaded with UNESCO World Heritage Sites filled with beautiful mosaics, several of which are easily recognizable from many history textbooks.

By the end of the fourth century CE, the Roman Empire had already experienced several periods of being governed by more than one emperor, each of whom having their own parts of it to rule. This style of governance became permanent in 395 with the death of Theodosius I, after whom the Western Roman Empire would be governed separately until its fall in 476.

At the beginning of the fifth century, the main centers of Roman power were Constantinople (now Istanbul) in the East and Mediolanum (now Milan) in the West. However, in 402 the capital of the West was moved to Ravenna to take advantage of the defensive value of the marshes surrounding the city, which added extra protection at a time when Goth, Vandal, and Hun invaders were increasingly becoming a serious security issue. It was for this reason that the Goths were able to sack Rome but not the capital at Ravenna in 410. (Also, it was the same type of threat which led to the construction of Venice in the middle of a lagoon just up the coast by people looking for a more secure and defensible place to live in the chaotic and dangerous world of the transition between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the dawn of the Middle Ages.)

The first sign of late antiquity that a visitor is likely to notice are the walls, which combined with the surrounding marshes provided the city with formidable defenses.

Most of the best-preserved monuments in town were built after the fall of the West in 476, but one of the few monuments built by the last of the Western Roman rulers of Ravenna is the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. She was the daughter of Theodosius I, who was held captive by the Goths and eventually married their leader in 414, and was later married to a Roman Emperor. Galla Placidia spent much of her later life as a powerful and influential woman in Roman politics. She was, however, never entombed in this mausoleum.

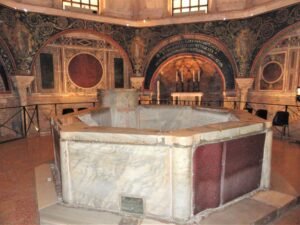

Also built in the fifth century is the Baptistery of Neon, which is also called the Orthodox Baptistery. It was once part of a basilica which was destroyed in the eighteenth century.

Another important baptistery is the Arian Baptistery, built by Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great, the king of the Ostrogoths who ruled over the Kingdom of Italy, which was established soon after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. However, the new kingdom did not survive long after Theodoric’s death in 526 as Justinian I, the ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire (which, for the period following the fall of the West, scholars today call the Byzantine Empire) conquered the Kingdom of Italy in 553. Theodoric was a follower of the Arian sect of Christianity, which at the time the Orthodox church considered a heresy, and thus there were both Orthodox (pictured above) and Arian (pictured below) baptisteries in the city, although both use the same motif to ornament the roof directly over the baptismal font.

Theodoric also built the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo to serve as his palace church. The architectural plan is similar to many other sixth-century churches built throughout the Christian world. Although it was originally an Arian church, the Byzantines reconsecrated it as an Orthodox church after conquering Italy. The church is lavishly decorated with splendid mosaics.

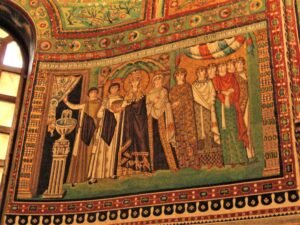

The most recognizable mosaics in town are found in the Basilica of San Vitale, which was also built in the period of Ostrogothic rule and consecrated just six years before the Byzantine conquest of Italy.

However, it is clear that much of the decoration of the church was added later by the Byzantine conquerors, as the two most recognizable mosaics in the central nave are the ones depicting Justinian I (left) and his wife, the Empress Theodora (right), each accompanied by an entourage.

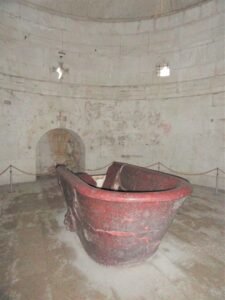

The mausoleum of Theodoric the Great is still standing in a park named after him in the northeastern outskirts of the city, although the Byzantines removed his body from it in order to repurpose the structure. The empty, broken sarcophagus in the center is made of porphyry.

Tips for the Visitor

Tips for the Visitor

Ravenna is on the regional train line which runs between Ferrara and Rimini, so it can easily be reached from anywhere in northern Italy with possibly a changeover in one of those cities.

The sites of interest of late antiquity are mostly concentrated in the center of the city, which is a relatively small area and can be navigated on foot.

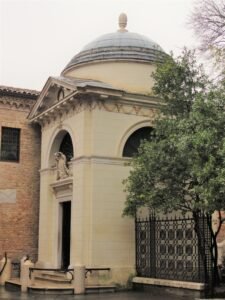

Although not ancient, one site of interest not be missed in central Ravenna is the tomb of the Renaissance poet Dante Alighieri (pictured here), author of The Divine Comedy, who died here in exile from his native Florence after backing a losing political faction. As a penance for exiling one of history’s greatest literary figures, the Commune of Florence continues to this day to pay for the oil in the lamps lighting the tomb’s interior.

If you are looking for more sites from late antiquity, head to the small town of Classe, just 5 km to the southeast. In antiquity, this was the port of Ravenna, although it is no longer on the coast. There, in addition to some archaeological ruins, you will find another beautiful church, the sixth-century Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, which is very similar in style and decor to the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in central Ravenna.

Location Map